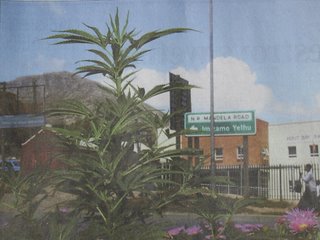

(IRIN) - You can smell the plant's sweet, peppery scent as it wafts through the Swazi bush in the mid-morning heat long before you see it.

After a 5km trek through the rugged terrain and tangled foliage that covers much of the country's northern Hhohho region, the unit of 30 police officers finally scrambled into a clearing.

Standing over six feet tall, row upon row of what they were looking for stretched out before them: hundreds of cannabis plants, also known as 'dagga' in this region, with the tools of the trade - shovels, plastic sheets and watering cans - scattered around its fringes; the growers were nowhere to be seen.

While it appeared to be a large find, the head of Swaziland's anti-drug unit, Supt Albert Mkhatshwa, who accompanied the search-and-destroy operation, maintained that such plantations were nothing out of the ordinary.

"This is just dagga being grown by some of the villagers close by. We will spray it with weed killer and the plants will be dead in a day or so, but if we come back in a month's time it is likely more will be growing in the same spot.

"The people know we don't have the necessary resources to cover the whole area, so they will take a chance that we will not come back soon. People have been growing herbal cannabis for a long time in Swaziland, long before it was illegal," he said.

Swaziland's climate and soil are conducive to growing the plant, and the people have known and used it for hundreds of years. However, over the last decade the combination of international demand and extreme poverty - about 70 percent of the country's one million people live on US$2 or less a day - has led to widespread cultivation.

The crop is grown in such large quantities that the United Nations Drug Control Programme has listed the country, which covers only 17,363sq.km, as one of the main cannabis-growing areas in southern Africa. The latest Interpol statistics estimate that east and southern Africa supplied 9 percent of the global $142 billion cannabis trade in 2004, with the region's major producers being identified as Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Swaziland and Tanzania.

'Swazi Gold' cannabis is internationally known for its potency - users experience a mild hallucinogenic affect when they ingest or smoke it - and consequently it is a highly sought after commodity in neighbouring South Africa as well as Europe.

An almost insatiable worldwide demand for the substance has attracted international crime syndicates to the country to fund and organise the large-scale production of dagga by locals.

According to South Africa's Institute for Security Studies (ISS), a regional think-tank, the financial proceeds are then used to fund other illegal activities.

"Of the cannabis that is harvested, the best quality is earmarked for compression into one- or two-kilogram blocks that are smuggled via South Africa and Mozambique to Europe and the UK [United Kingdom]," said a recent ISS report on Swaziland's cannabis trade.

"Nigerian criminal networks have moved into the dominant position in the Swazi cannabis trade during the past few years, and the proceeds of their sales in Europe are used to pay for cocaine purchased in South America, which is then smuggled to South Africa and elsewhere."

After consulting police experts in Swaziland and the European Union (EU), the ISS revealed that growers at the point of sale in Swaziland received between $45 and $52 per kilogram, depending on quality. However, once the narcotic has reached the EU's streets its retail value is about 140 times that amount, with high-quality Swazi Gold fetching as much as US$7,600 a kilogram in the UK.

So far, the limited success of the Swazi police in controlling the illegal trade has coincided with locating the plants before they were harvested. Once compressed and packaged, consignments are taken into neighbouring countries using back roads, or simply through holes cut in the border fence, which are "notoriously difficult to monitor," said Supt Mkhatshwa.

The successes in the field were largely due to assistance given by the South African and United States governments, both of which provided specialised equipment, such as helicopters and off-road vehicles, to help the anti-drug units locate plantations grown in areas not easily accessible by road.

South Africa recently withdrew its assistance, leaving the Swazi police to tackle the problem with the meagre resources at their disposal.

South African Police spokesperson Ronan Naidoo said the South African government had assisted the Swazi police with aerial surveys and crop spraying aircraft in the past, but co-operation on operations was no longer in place because of escalating costs. "There have been many joint operations, but they have to involve a joint covering of the expenses involved for them to continue," he told IRIN.

Swaziland, ruled by King Mswati III, sub-Sahara's last absolute monarch, saw its economy contract from 2.1 percent growth, last year to 1.8 percent this year, while the population increased by 2.9 percent, the central bank said in a report to the government this month.

Consequently, Supt Mkhatshwa now dispatches his anti-drug units into dense bush and mountainous areas on foot, with nothing more than a container of weed killer on their backs and a spray gun in their hands.

"I send men into the bush to survey the areas for the dagga plantations and once they find a sizable crop a larger group goes back and sprays the area. We are doing this every two weeks, but it is not having much impact.

"A couple of years ago the South Africans did aerial surveys for us over the inaccessible regions, and when they found plantations they either sprayed them from the air or flew us in to spray them. This co-operation enabled us to rid ourselves of large amounts of dagga growing in areas that take a full day to get to by foot," he said.

The latest statistics compiled by the Swazi anti-drug unit show that in the first seven months of this year 2,407kg of compressed cannabis was seized, and a further 356.5ha of cannabis plantations were destroyed.

"If we were able to do real surveys we would be able to destroy lots more than we have done. It is so difficult to reach the plantations in the mountainous areas. Often times they are so large that we are not able to carry enough chemicals to spray all the plants. Unless we get help, this [problem] will become extremely difficult to control," he said.

Open this Placemark

Open this Placemark

Download here:

Download here: